**TL;DR**

Web scraping with Python is one of the most practical ways to turn public web pages into structured, usable data. With the right setup and libraries, Python lets you build custom scrapers that collect data reliably, adapt to changing websites, and scale as your needs grow. This guide walks through the fundamentals, from environment setup and HTML parsing to handling dynamic content, common scraping challenges, and best practices for storing and managing scraped data.

Introduction to Web Scraping with Python

Web data is everywhere. Prices change daily, product catalogs update constantly, reviews pile up by the minute, and entire websites act as living data sources. For teams that rely on timely information, manually copying data from pages is slow, error-prone, and impossible to scale. This is why web scraping with Python has become a core skill for developers, analysts, and data engineers.

Python stands out because it lowers the barrier to entry while still offering enough power for complex scraping tasks. Its syntax is easy to read, its ecosystem is mature, and its libraries cover everything from simple HTTP requests to full browser automation. Whether you are pulling a few pages for research or building a pipeline that runs every day, Python gives you the flexibility to start small and grow.

What makes custom Python scrapers especially valuable is control. You decide what data to extract, how often to run the scraper, how to clean the output, and how to store it. This level of customization is difficult to achieve with off-the-shelf tools alone, especially when websites change structure or load content dynamically.

In this refreshed guide, we focus on practical, real-world scraping. We start with the basics of setting up a Python environment, then move through HTML structure, selectors, and writing your first scraper. From there, we cover common challenges like pagination, JavaScript-rendered pages, and rate limiting, before ending with guidance on storing and managing scraped data responsibly.

If you want to understand not just how scraping works, but how to build scrapers that last, this is where to begin.

Why Python Is Ideal for Building Custom Web Scrapers

Python has become the default choice for developers building custom scraping tools, not because it is trendy, but because it strikes the right balance between simplicity and control. When teams adopt web scraping with Python, they gain flexibility without committing to heavy infrastructure too early.

Here is why Python works so well in real-world scraping projects.

Readable syntax that speeds up iteration

Scrapers break. Websites change. Logic needs constant adjustment. Python’s readable syntax makes it easier to debug, update selectors, and tweak extraction rules without rewriting entire scripts. This matters when scrapers must be maintained over months or years.

A developer can return to a Python scraper after weeks and still understand what it does. That alone saves time and reduces errors.

A mature ecosystem built specifically for scraping

Python’s ecosystem covers every scraping scenario you are likely to encounter.

Commonly used tools include:

- requests for reliable HTTP communication

- BeautifulSoup for fast HTML parsing

- lxml for performance-heavy parsing tasks

- Selenium or Playwright for JavaScript-rendered pages

- Scrapy for larger crawling and pipeline-based workflows

These libraries work well together, letting you combine simple scripts with more advanced logic as complexity grows.

Easy handling of structured and unstructured data

Web data is messy. Prices appear as text. Tables mix numbers and strings. Reviews arrive as long paragraphs. Python handles all of this cleanly. Built-in data structures like lists and dictionaries make it easy to transform raw page content into structured formats.

This makes Python especially strong when scraped data must feed analytics, machine learning models, or downstream APIs.

Scales from scripts to systems

Many scraping projects start as one-off scripts. Over time, they turn into scheduled jobs, pipelines, or services. Python supports this evolution naturally. A single file script can grow into a modular project with logging, retries, monitoring, and storage layers.

You do not need to switch languages as requirements change.

Strong community and long-term stability

Python scraping libraries are actively maintained, well-documented, and widely used. When a website introduces new protections or rendering patterns, the community adapts quickly. This reduces long-term risk compared to niche tools.

For teams building scrapers that need to survive website changes, this stability matters.

Want reliable, structured Temu data without worrying about scraper breakage or noisy signals? Talk to our team and see how PromptCloud delivers production-ready ecommerce intelligence at scale.

Setting Up Your Python Environment for Web Scraping

Before writing any scraping logic, a clean and predictable environment matters more than people expect. Most scraping issues are not caused by selectors or parsing. They come from mismatched dependencies, broken installs, or scripts running in the wrong context. A proper setup saves time later.

Install Python correctly

Start by installing the latest stable version of Python 3 from the official Python website. Avoid system-level Python installations that come preinstalled with some operating systems. They are often outdated and can cause conflicts.

After installation, confirm everything works by running:

python –version

This should return a Python 3.x version number.

Use a virtual environment

Virtual environments isolate project dependencies. This prevents library conflicts and keeps your scraping setup reproducible.

From your project directory, create a virtual environment:

python -m venv venv

Activate it:

- On Windows:

venvScriptsactivate

- On macOS or Linux:

source venv/bin/activate

Once activated, all installed packages remain scoped to this project only.

Install core scraping libraries

Most projects start with a small, reliable stack:

pip install requests beautifulsoup4

These two libraries handle the majority of static scraping tasks. You can expand later if you need browser automation or crawling frameworks.

Optional additions as complexity grows:

- lxml for faster parsing

- selenium or Playwright for JavaScript-heavy sites

- scrapy for large-scale crawling

Verify the setup

Open a Python shell and import the libraries:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

If no errors appear, the environment is ready.

Keep dependencies explicit

As projects grow, always freeze dependencies:

pip freeze > requirements.txt

This ensures anyone running the scraper later uses the same versions you tested.

A clean setup may feel slow at first, but it prevents silent failures when scrapers run unattended. Once this foundation is in place, you can focus on extraction logic instead of environment fixes.

Understanding HTML Structure and CSS Selectors

Every scraper lives or dies by how well it understands the structure of a web page. Before writing extraction logic, you need to know how content is organized and how to target it precisely. This is where HTML structure and CSS selectors come in.

How web pages are structured

Web pages are built using HTML. Think of HTML as a tree. At the top is the <html> tag, followed by <head> and <body>. Everything visible on a page lives inside the body as nested elements.

Common elements you will encounter include:

- <div> for layout and grouping

- <p> for text

- <a> for links

- <img> for images

- <table>, <tr>, <td> for tabular data

- <span> for inline content

Each element can carry attributes like class, id, href, or src. These attributes are what you use to identify and extract the data you want.

Why attributes matter for scraping

Most useful data is not identified by tag alone. Pages often contain dozens of similar elements. Attributes help narrow your target.

For example:

- class groups similar elements

- id uniquely identifies a single element

- custom attributes often store metadata

Scrapers rely on these attributes to stay precise.

What CSS selectors do

CSS selectors are patterns that tell your scraper exactly which elements to select. They allow you to express relationships between elements without hardcoding fragile logic.

Common selector types include:

- Tag selectors

Select elements by tag name.

Example: p selects all paragraph elements. - Class selectors

Select elements by class.

Example: .price selects all elements with class price. - ID selectors

Select a specific element by ID.

Example: #header selects the element with id header. - Attribute selectors

Select elements based on attributes.

Example: img[src] selects all image tags with a source attribute. - Combined selectors

Select elements based on hierarchy.

Example: div.product h2 selects headings inside product containers.

Inspecting pages correctly

Before scraping, always inspect the page using browser developer tools. Look at:

- repeated patterns across items

- stable class names instead of generated ones

- parent containers that group related data

Avoid selectors tied to visual layout rather than content meaning. Layout changes more often than structure.

Keeping selectors resilient

Websites change. To reduce breakage:

- prefer semantic classes over positional selectors

- avoid deep chains unless necessary

- test selectors across multiple pages

Strong selectors make scrapers easier to maintain and less fragile over time.

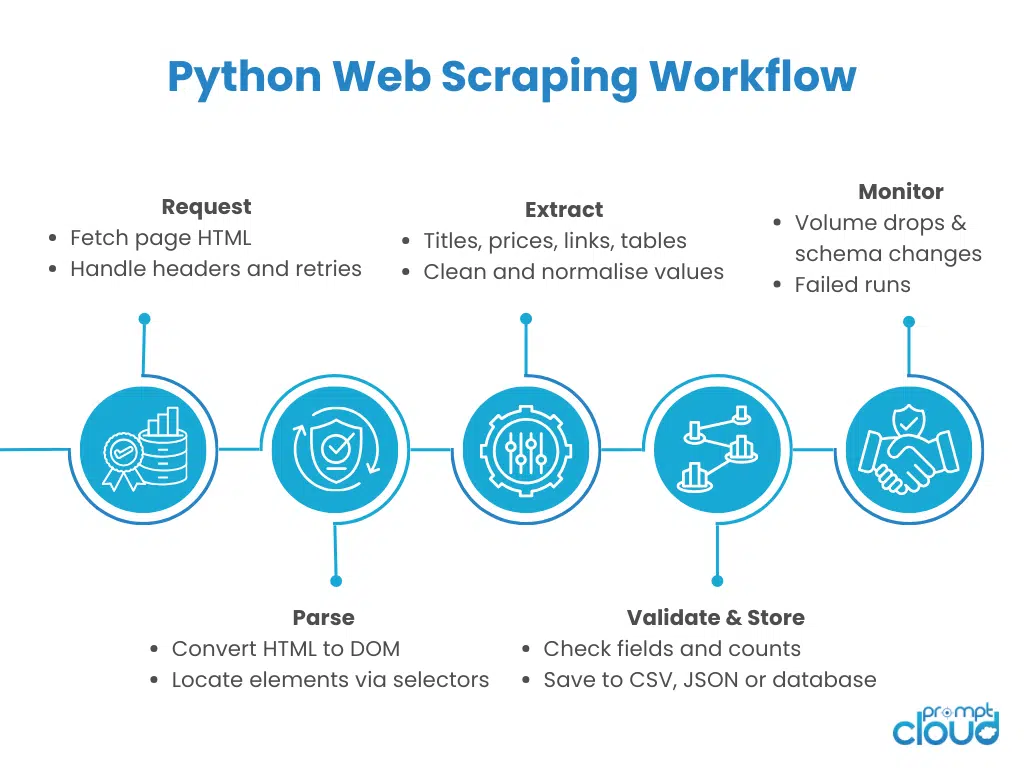

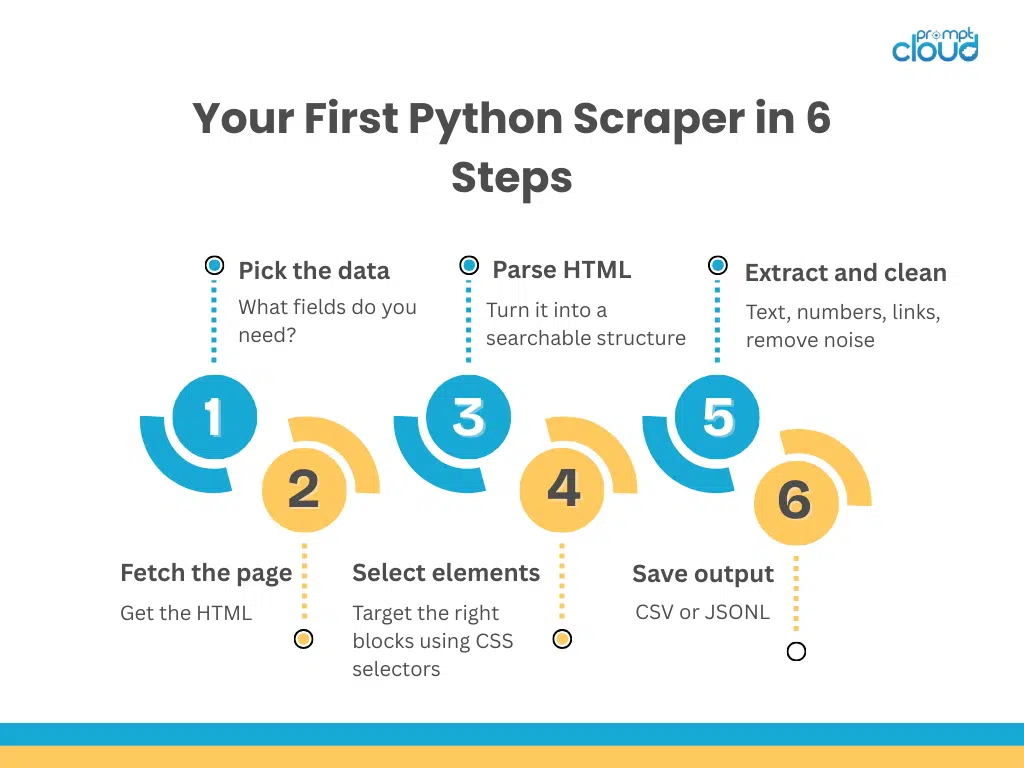

Writing Your First Python Scraper Step by Step

Once you understand page structure and selectors, the actual scraping logic becomes straightforward. The goal is not to build something complex on day one, but to create a small, reliable script that fetches a page, parses it, and extracts exactly what you need.

Step 1: Decide what data you want

Before touching code, be clear about the output.

- Are you extracting titles, prices, links, or tables

- Is it a single page or multiple pages

- Does the data repeat in a predictable pattern

Scrapers fail most often because this step is skipped.

Step 2: Fetch the page

At a basic level, scraping starts with making an HTTP request to a URL and retrieving its HTML response. This gives you the raw page content exactly as the server returns it.

At this stage, you are not interacting with the browser, just downloading the page source.

Step 3: Parse the HTML

Raw HTML is difficult to work with directly. Parsing converts it into a structured object that you can query using selectors.

This parsed structure allows you to:

- search by tag

- filter by class or attribute

- loop through repeating elements

Once parsed, the page becomes a searchable tree rather than a long string of text.

Step 4: Locate the target elements

Using browser inspection, you identify the container that holds your data. Most websites repeat product cards, rows, or blocks using the same structure.

Instead of targeting individual fields immediately, start by selecting the outer container. From there, extract child elements such as:

- title text

- price values

- URLs

- image sources

This approach keeps the logic clean and easier to update later.

Step 5: Extract and clean the data

Extracted values often include extra whitespace, symbols, or formatting artifacts. Cleaning ensures consistency.

Common cleanup steps include:

- trimming whitespace

- removing currency symbols

- normalizing text casing

- converting strings to numbers

Clean data is more valuable than raw data.

Step 6: Store the results

Once extracted, data should be stored in a structured format. For small projects, flat files work well. For larger workflows, databases or APIs are more appropriate.

Typical formats include:

- CSV for tabular datasets

- JSON for nested or hierarchical data

- direct insertion into databases

Choosing the format early helps align scraping with downstream usage.

Step 7: Validate before scaling

Before expanding to hundreds or thousands of pages:

- verify data completeness

- check for missing fields

- confirm selectors work across pages

Scaling a broken scraper only multiplies errors.

At this point, you have a functional scraper that follows a clean, repeatable process. In the next section, we will look at common challenges that appear once scrapers move beyond simple pages and how to handle them without rewriting everything from scratch.

Handling Real-World Scraping Challenges at Scale

Once your scraper works on a single page, reality sets in. Most production scraping problems do not come from writing code, but from how websites behave at scale. This is where many DIY scrapers start breaking.

Pagination and infinite scroll

Product lists, news feeds, and search results rarely sit on one page.

Common patterns you will encounter:

- page-based URLs with query parameters

- infinite scroll loading content dynamically

- “Load more” buttons triggered by user actions

A reliable scraper must detect how new data is loaded and replicate that behavior programmatically. For pagination, this often means iterating predictable URL patterns. For infinite scroll, it means capturing the underlying network requests that load additional data.

Dynamic content and JavaScript rendering

Many modern websites do not expose full data in the initial HTML response. Instead, content loads through JavaScript calls after the page renders.

In these cases:

- basic HTTP requests return incomplete pages

- key fields like prices or reviews appear missing

- selectors work in the browser but fail in code

This is where browser-level automation or JavaScript rendering becomes necessary. The goal is not to render everything blindly, but to identify which requests actually return the structured data you need.

Anti-bot detection and request blocking

As request volume increases, websites start watching traffic patterns.

Common signals that trigger blocks:

- high request frequency

- repeated requests from the same IP

- identical headers across requests

- missing browser-like behavior

When this happens, scrapers may start returning empty responses, error pages, or CAPTCHA challenges. Slowing request rates, rotating identities, and mimicking real browsers becomes critical once scraping moves beyond experimentation.

Rate limits and stability issues

Even without aggressive blocking, websites often enforce implicit limits.

If requests are too fast:

- responses slow down

- timeouts increase

- data becomes inconsistent

Stable scrapers prioritize consistency over speed. A slower scraper that runs reliably every day is more valuable than a fast one that fails unpredictably.

Website structure changes

Websites evolve constantly.

Small changes such as:

- renamed class attributes

- additional wrapper elements

- reordered fields

can silently break extraction logic. This is why scrapers should be built with resilience in mind, using structural patterns instead of brittle selectors wherever possible.

Data validation and monitoring

Scraping does not end when data is collected.

Production-grade workflows include:

- schema validation to catch missing fields

- freshness checks to detect stalled updates

- alerts when extraction volume drops unexpectedly

Without monitoring, failures may go unnoticed for weeks.

At this stage, it becomes clear why teams often start with custom scripts and later transition to managed scraping pipelines. In the final section, we will look at when building in Python makes sense and when it becomes a maintenance burden, and how teams decide the right approach.

Example: A starter scraper that handles pagination, retries, and CSV output

This is the pattern most custom scrapers follow in production: make polite requests, retry failures, parse with stable selectors, and write rows to a CSV.

import csv

import random

import time

from urllib.parse import urljoin

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from requests.adapters import HTTPAdapter

from urllib3.util.retry import Retry

def make_session() -> requests.Session:

session = requests.Session()

# Retry strategy for transient failures

retries = Retry(

total=5,

backoff_factor=0.7,

status_forcelist=[429, 500, 502, 503, 504],

allowed_methods=[“GET”],

raise_on_status=False,

)

adapter = HTTPAdapter(max_retries=retries)

session.mount(“http://”, adapter)

session.mount(“https://”, adapter)

# Browser-like headers help with basic blocking

session.headers.update(

{

“User-Agent”: (

“Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) “

“AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) “

“Chrome/120.0.0.0 Safari/537.36”

),

“Accept-Language”: “en-US,en;q=0.9”,

}

)

return session

def polite_sleep(min_s: float = 1.0, max_s: float = 2.5) -> None:

time.sleep(random.uniform(min_s, max_s))

def parse_list_page(html: str, base_url: str) -> tuple[list[dict], str | None]:

“””

Update selectors to match your target site.

Assumes:

– Each item is inside an element like: <div class=”product-card”>…</div>

– Title in: <h2 class=”title”>…</h2>

– Price in: <span class=”price”>…</span>

– Product link in: <a class=”product-link” href=”/p/123″>…</a>

– Next page link in: <a rel=”next” href=”?page=2″>Next</a>

“””

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, “html.parser”)

rows: list[dict] = []

for card in soup.select(“div.product-card”):

title_el = card.select_one(“h2.title”)

price_el = card.select_one(“span.price”)

link_el = card.select_one(“a.product-link”)

title = title_el.get_text(strip=True) if title_el else “”

price = price_el.get_text(strip=True) if price_el else “”

product_url = urljoin(base_url, link_el[“href”]) if link_el and link_el.get(“href”) else “”

if title or price or product_url:

rows.append(

{

“title”: title,

“price”: price,

“url”: product_url,

}

)

next_el = soup.select_one(‘a[rel=”next”]’)

next_url = urljoin(base_url, next_el[“href”]) if next_el and next_el.get(“href”) else None

return rows, next_url

def scrape_paginated(start_url: str, out_csv: str, max_pages: int = 10) -> None:

session = make_session()

current_url = start_url

page_count = 0

with open(out_csv, “w”, newline=””, encoding=”utf-8″) as f:

writer = csv.DictWriter(f, fieldnames=[“title”, “price”, “url”])

writer.writeheader()

while current_url and page_count < max_pages:

resp = session.get(current_url, timeout=25)

# Basic guardrails

if resp.status_code == 403:

raise RuntimeError(“Blocked (403). Slow down, adjust headers, or use a different approach.”)

if resp.status_code == 429:

# Too many requests: back off more aggressively

time.sleep(10 + random.uniform(0, 5))

continue

resp.raise_for_status()

rows, next_url = parse_list_page(resp.text, base_url=current_url)

for row in rows:

writer.writerow(row)

page_count += 1

current_url = next_url

polite_sleep()

print(f”Done. Wrote {out_csv} from {page_count} page(s).”)

if __name__ == “__main__”:

# Replace with a real category/listing URL you have permission to scrape

scrape_paginated(

start_url=”https://example.com/products?page=1″,

out_csv=”products.csv”,

max_pages=20,

)

Please note:

- Update the CSS selectors inside parse_list_page() to match their target site’s HTML.

- Replace start_url with the real listing page.

- Adjust max_pages, sleep range, and error handling based on rate limits.

Which Python approach fits which scraping situation

| Scenario | Best approach | Why it fits | Typical tradeoff |

| Static pages, simple HTML | requests + BeautifulSoup | Fast to build, easy to maintain for small jobs | Breaks if data loads via JavaScript |

| Many pages, crawling at scale | Scrapy | Built-in concurrency, pipelines, retries, throttling | More setup, steeper learning curve |

| JavaScript-rendered content | Playwright or Selenium | Renders pages like a real browser, can scroll/click | Slower, heavier, needs careful scaling |

| Data hidden behind XHR calls | requests + API-style calls | Often faster than browser automation | Requires inspecting network calls |

| Strict blocking / frequent layout changes | Managed scraping | Less maintenance burden, higher reliability | Less DIY control, external dependency |

Hardening Your Python Scraper for Real Sites

That starter script will work on friendly pages. The moment you point it at real production sites, you will want a few upgrades so it does not fail silently or produce messy output.

1. Add a clear schema, then validate every row

Decide what fields are mandatory for your use case. For example, title and url. If a page suddenly returns empty titles, that is usually a selector break, not “no data.”

Practical validation rules that catch most issues:

- required fields are not empty

- price parses into a number when expected

- URLs are absolute and valid

- counts do not drop sharply compared to yesterday

When a row fails validation, save it to a separate “rejects” file with the raw HTML snippet or the page URL for debugging.

2. Log what matters, not everything

If you ever run scrapers on a schedule, print statements stop being enough.

Log at minimum:

- start time, end time

- number of pages fetched

- number of items extracted

- number of items rejected by validation

- non-200 responses and retries

- the final next page URL you saw

This makes failures explainable in minutes instead of hours.

3. Treat selectors as configuration

Hardcoding selectors inside code makes small site changes painful.

A more maintainable pattern:

- keep selectors in one place

- name them clearly, like product_card, title, price, next_page

- store them in a JSON or YAML config if you support multiple sites

Then you update selectors without touching core logic.

4. Prefer network calls over browser automation when possible

Many sites load listings through XHR calls returning JSON. If you can identify those endpoints in DevTools, scraping becomes more stable and faster than rendering full pages.

A simple rule:

- if the data is returned as JSON, scrape the JSON

- if the data only appears after render and interaction, use Playwright or Selenium

5. Build for “polite” scraping from day one

Even when allowed, aggressive traffic gets blocked. You already added sleep. Keep it.

Add practical safeguards:

- cap concurrency per domain

- randomize delays within a range

- retry only on transient failures like 429 and 5xx

- stop after repeated 403 blocks and alert instead of hammering

6. Make storage decisions early

If the scraper is just a one-off, CSV is fine. If this becomes recurring, move toward:

- JSON Lines for flexible records

- a database for querying and dedupe

- object storage for large payloads like HTML snapshots or images

Also store a small “run manifest” per scrape, with the date, run ID, and counts. It pays off later when someone asks, “when did this start breaking?”

7. Add a basic change detector

Most scrapers do not fail loudly. They fail quietly by extracting fewer items.

A simple weekly guardrail:

- compare extracted item count against a rolling baseline

- alert if it drops by more than a threshold, like 30 percent

- sample a few pages and confirm key fields are still present

This prevents data pipelines from drifting for weeks unnoticed.

Scraping Dynamic Content with Playwright

When requests + BeautifulSoup returns “empty” pages, it usually means the content is rendered by JavaScript after the initial HTML loads. In those cases, you have two practical options:

- Find the underlying XHR or JSON endpoint and scrape that directly.

- Render the page with a headless browser and extract after the content loads.

If you can scrape the JSON, do that. It is faster and more stable. If the site only reveals data after render, use Playwright.

How to decide: render vs API call

| Signal you see in DevTools | Best approach | Why |

| Network tab shows XHR returning JSON with the fields you need | Direct API-style requests | Faster, fewer moving parts, less brittle |

| Data appears only after scroll, click, or filters change the page | Playwright rendering | You need interaction to trigger data |

| HTML source view is missing prices, reviews, or listings | Playwright or XHR scraping | Server HTML is incomplete |

| Heavy anti-bot triggers on plain requests | Playwright first, then optimize | Browser-like behavior often passes basic checks |

Minimal Playwright example: render, scroll, extract cards, paginate

import asyncio

import csv

from urllib.parse import urljoin

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

from playwright.async_api import async_playwright

async def scrape_listing_pages(start_url: str, out_csv: str, max_pages: int = 5) -> None:

async with async_playwright() as p:

browser = await p.chromium.launch(headless=True)

page = await browser.new_page()

current_url = start_url

page_count = 0

with open(out_csv, “w”, newline=””, encoding=”utf-8″) as f:

writer = csv.DictWriter(f, fieldnames=[“title”, “price”, “url”])

writer.writeheader()

while current_url and page_count < max_pages:

await page.goto(current_url, wait_until=”networkidle”, timeout=60000)

# If the site lazy-loads, scroll a bit to trigger images/cards

for _ in range(4):

await page.mouse.wheel(0, 1200)

await page.wait_for_timeout(800)

html = await page.content()

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, “html.parser”)

# Update selectors to match the site

for card in soup.select(“div.product-card”):

title_el = card.select_one(“h2.title”)

price_el = card.select_one(“span.price”)

link_el = card.select_one(“a.product-link”)

title = title_el.get_text(strip=True) if title_el else “”

price = price_el.get_text(strip=True) if price_el else “”

url = urljoin(current_url, link_el[“href”]) if link_el and link_el.get(“href”) else “”

if title or price or url:

writer.writerow({“title”: title, “price”: price, “url”: url})

# Pagination: prefer a real “next” link if present

next_el = soup.select_one(‘a[rel=”next”]’)

current_url = urljoin(current_url, next_el[“href”]) if next_el and next_el.get(“href”) else None

page_count += 1

await browser.close()

if __name__ == “__main__”:

# Install once:

# pip install playwright beautifulsoup4

# playwright install

asyncio.run(

scrape_listing_pages(

start_url=”https://example.com/products?page=1″,

out_csv=”products_playwright.csv”,

max_pages=10,

)

)

Practical notes that prevent pain later

- Use wait_until=”networkidle” as a starting point, then add targeted waits if the site is still flaky.

- Do not scroll blindly forever. Scroll a fixed number of times, then extract, then paginate.

- Treat Playwright as the “last mile” tool. If you can replace it with direct JSON calls later, do it. Your runtime and infra costs will drop immediately.

Storing Scraped Data Cleanly

Once extraction works, storage becomes the difference between “I scraped it” and “I can use it.” A lot of scraping projects fail here because the output is inconsistent, hard to join, or impossible to audit later.

Pick a storage format based on how you will use the data

CSV

- Best when your data is truly tabular and stable.

- Easy for analysts and quick checks.

- Weak for nested fields like variants, images, or multi-level attributes.

JSON Lines (JSONL)

- Best default for scraping pipelines.

- One record per line, flexible schema, easy to append.

- Works well when fields evolve or some fields are optional.

Database

- Best when you need querying, deduplication, and incremental updates.

- Use Postgres for structured data.

- Use MongoDB when records are nested and the schema evolves.

A practical pattern many teams use:

- Write JSONL as the raw output.

- Load cleaned data into a database or warehouse.

Always write a run manifest

Treat each scrape run like a batch job that must be explainable later.

A simple manifest file per run should include:

- run_id

- start_time, end_time

- target_domain

- pages_fetched

- items_extracted

- items_written

- items_rejected

- status and top errors

This sounds boring. It is also what saves you when someone asks why yesterday’s dataset is half the size.

Add lightweight validation before writing

Validation is not a huge framework. It is a few rules that stop garbage from entering your dataset.

Examples that catch most real-world breakages:

- title and url must exist

- price must parse to a number if present

- extracted count should not drop sharply compared to baseline

- required fields should not be blank across an entire page

When a record fails validation:

- write it to rejects.jsonl

- include the page URL and a short reason like missing_title or price_parse_failed

Make dedupe part of storage, not an afterthought

At scale, duplicates become normal. They show up across pages, across runs, and across regions.

Two simple approaches:

- Deduplicate within a run using a key like product_id or url.

- Deduplicate across runs by storing a stable key and using upsert logic in a database.

Keep raw and cleaned outputs separate

A clean workflow usually has two layers:

- raw: what you scraped, minimally processed

- clean: normalized fields, consistent types, deduped records

This separation makes debugging easy when a source site changes.

When Building Custom Scrapers with Python Makes Sense

Building your own scraping tools with Python gives you control. You decide what to collect, how often to run it, how strict validation should be, and where the data finally lands. For teams experimenting, learning, or solving a narrowly scoped problem, this flexibility is powerful. A well-written Python scraper can answer very specific questions quickly, without waiting on external dependencies.

That said, most teams discover a pattern over time.

They start with a script.

Then they add retries.

Then validation.

Then logging.

Then scheduling.

Then monitoring.

Slowly, the scraper turns into a system.

At that point, the real challenge is no longer writing Python code. It is keeping the data reliable as websites change, traffic grows, and business expectations increase. Layout changes break selectors. Anti-bot systems tighten. Volumes increase. Stakeholders expect fresh data every morning, not “the script failed last night.”

Python remains an excellent foundation through all of this. The same skills you use to build your first scraper apply when you later evaluate whether to scale it, refactor it, or replace parts of it with managed pipelines. Understanding how scraping works at a low level helps you make better architectural decisions later.

The most effective teams are not dogmatic. They build in Python when it makes sense, automate responsibly, and switch approaches when maintenance cost starts exceeding insight value. The goal is not scraping for its own sake. The goal is dependable, usable data that feeds real decisions.

If you have reached the point where scraping logic is stable but operational overhead keeps growing, that is usually the signal to rethink how extraction is handled, not what language you used.

Python gets you started quickly. Good engineering judgment keeps you moving forward.

If you want to explore more

- Learn practical patterns in scraping using Python to understand real-world extraction workflows.

- Go deeper with a hands-on web scraping Python guide covering tools and approaches.

- Build foundational understanding with this guide to web scraping for different business use cases.

For a clear, practical understanding of how websites load content, handle requests, and structure pages, refer to MDN Web Docs on HTTP and HTML fundamentals. This resource helps scraping practitioners understand DOM structure, request headers, responses, and client side rendering behavior, which directly impacts extraction reliability.

Want reliable, structured Temu data without worrying about scraper breakage or noisy signals? Talk to our team and see how PromptCloud delivers production-ready ecommerce intelligence at scale.

FAQs

1. Is Python still a good choice for web scraping in 2025?

Yes. Python remains one of the most practical choices because of its mature ecosystem, readability, and flexibility. Libraries for HTTP requests, parsing, browser automation, and scheduling continue to evolve, making Python suitable for both small scripts and production-grade scraping workflows.

2. What is the biggest risk when building custom scrapers in Python?

The biggest risk is silent failure. Websites change structure frequently, and scrapers may continue running while extracting incomplete or incorrect data. Without validation, logging, and monitoring, teams often realize issues weeks later, when downstream analysis is already affected.

3. How do I know if a site can be scraped using simple requests instead of browser automation?

Open the browser’s developer tools and check the Network tab. If product data or listings appear in XHR responses as JSON, direct requests usually work. If the data only appears after scrolling or clicking, browser automation becomes necessary.

4. Can Python scrapers scale to millions of pages?

They can, but scaling introduces operational complexity. You will need concurrency control, proxy management, error handling, retries, storage optimization, and monitoring. At high scale, maintenance effort often outweighs the benefit of fully custom scripts.

5. When should teams stop building scrapers themselves?

When scraping becomes business-critical and uptime, freshness, and compliance matter more than experimentation. If your team spends more time fixing scrapers than using the data, it is usually time to consider managed extraction pipelines.