**TL;DR**

Web scraping isn’t illegal by default. It also isn’t automatically safe. Most of the trouble comes from context, not intent. What kind of data you’re pulling, how you’re accessing it, where it lives, and what you plan to do with it later all matter more than the act of scraping itself. Laws don’t treat all web data the same, and they don’t treat all use cases equally either. This piece walks through how different regions think about scraping, how rules like GDPR actually show up in real pipelines, where copyright lines get blurry, and why a little judgment goes a long way. If you work with web data, this is about knowing where the ground is solid before you step.

Why Web Scraping Law Creates So Much Confusion

If you ask different teams whether web scraping is legal, the answers usually reflect experience rather than accuracy. Recently, laws and court interpretations have not been ratified. Privacy frameworks expanded. Copyright boundaries were tested. Platforms adjusted access controls. Businesses kept building faster than the rules evolved. The result is an uneven landscape. Some teams push forward without guardrails.

What Web Scraping Legal Really Refers To

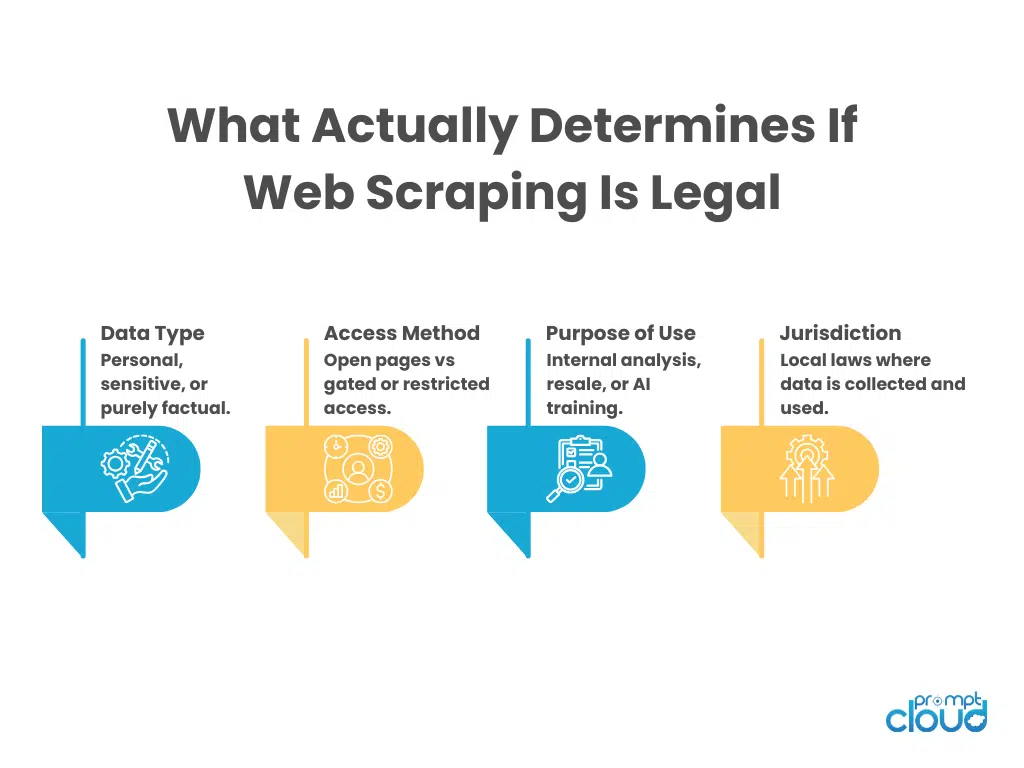

The more useful question is whether a specific data collection setup is lawful under specific conditions. Regulators and courts do not assess scraping in the abstract. They look at a combination of factors.

Figure 1: The four core factors regulators and courts evaluate when determining whether a web scraping activity is lawful.

The type of data is the first filter. Information about products, prices, or schedules is treated very differently from information that can be tied to an individual. The moment data starts pointing to a person, legal obligations increase.

The access path is the second filter. Collecting data that any visitor can see without logging in is not evaluated the same way as accessing restricted areas. Using automation is not the issue. Circumventing controls is. The purpose of use is the third filter. Data gathered for internal analysis may face fewer constraints than data reused commercially or fed into large-scale models. Some jurisdictions explicitly consider downstream use when assessing legality.

PromptCloud helps build structured, enterprise-grade data solutions that integrate acquisition, validation, normalization, and governance into one scalable system.

How Different Regions Approach Web Scraping

United States

In the United States, Data that is openly available to the public is often treated as fair to collect, provided the collector does not bypass login systems, technical barriers, or explicit access restrictions. The reasoning is that information exposed to the open web carries a lower expectation of control. That said, legality is not unconditional.

European Union

The European Union evaluates scraping primarily through the lens of data protection. GDPR does not prohibit automated collection. It regulates how personal data is handled. If a dataset contains no personal information, GDPR is usually irrelevant. Many analytics and pricing use cases fall into this category. Public visibility does not remove these obligations.

Asia-Pacific Regions

Some countries focus heavily on consent and data localization. Others prioritize platform rights and content ownership. Emerging regulations increasingly address automated access, especially when it affects platform stability or consumer privacy.

For global teams, this means pipelines must be flexible. Region-aware routing, selective field collection, and localized retention policies are becoming standard practice.

GDPR Scraping: What Actually Triggers Risk (and What Doesn’t)

GDPR is often treated as a blanket restriction on web scraping. That belief causes more confusion than clarity. GDPR does not regulate scraping as a technical activity. It regulates how personal data is processed. Understanding this distinction changes how teams design pipelines and assess risk.

The first question GDPR asks is simple. Does the dataset contain personal data. Many datasets used in pricing intelligence, product tracking, market monitoring, or content analysis fall into this category. Product names, prices, specifications, stock status, and aggregate signals are not personal data.

Risk appears when scraping pipelines collect or infer information that can identify an individual. Names, usernames, profile links, photos, email addresses, phone numbers, location signals, and identifiers tied to a person all fall under GDPR’s scope. Public visibility does not remove protection.

Where teams get into trouble is assuming that publicly available personal data is exempt. GDPR explicitly rejects that idea. Public does not mean unregulated.

What actually triggers GDPR risk

Purpose expansion

Data collected for one purpose cannot automatically be reused for another. Scraping data for research and later using it for AI training without reassessment creates compliance gaps.

Over-collection

Scraping more fields than necessary increases exposure. GDPR favors minimal collection tied directly to a defined purpose.

Uncontrolled retention

Keeping personal data indefinitely violates GDPR principles. Retention windows must be defined and enforced.

What does not automatically trigger GDPR

Scraping non-personal public data

Prices, product attributes, availability, and aggregated metrics remain outside GDPR scope.

Automated access alone

GDPR does not prohibit automation. It regulates data type and usage, not the scraping mechanism.

Why GDPR pushes better pipeline design

GDPR has indirectly improved data quality practices. Teams now filter sensitive fields earlier, document data lineage more clearly, and design pipelines that can explain how data moves and why it exists.

This discipline benefits AI systems. Cleaner inputs reduce noise. Clear purpose boundaries prevent unintended reuse. Structured governance makes models easier to maintain and defend.

GDPR compliance is not about stopping scraping. It is about controlling what enters the pipeline and how long it stays there. Teams that understand this build systems that scale without accumulating silent legal risk.

Copyright Law, Fair Use, and Scraped Data

Copyright law introduces a different kind of complexity into web scraping. A product price is a fact. A news article explaining that price movement is a creative expression. Scraping one is generally treated very differently from scraping the other. Where teams struggle is assuming that public access implies free reuse.

Where fair use enters the picture

Fair use evaluates purpose, transformation, amount used, and market impact. Transformative uses, such as analysis or pattern extraction, may qualify. Direct reproduction usually does not.

Fair use is not automatic. It is context-dependent and often determined after the fact. This uncertainty is why teams should not rely on fair use as their primary defense.

How copyright affects AI training

Using scraped content to train AI models is now under active legal scrutiny globally. Courts are evaluating whether model training is sufficiently transformative and whether it harms the original creator’s market.

This uncertainty makes governance and selectivity essential. Teams that train models on clearly factual, non-creative data face far lower risk than those ingesting large volumes of expressive content.

Table — How Copyright Applies to Common Scraped Data Types

| Data Type | Copyright Risk Level | Why It Matters |

| Product prices and availability | Low | Considered factual information |

| Technical specifications | Low | Facts are not protected |

| User reviews | Medium | May include creative expression and personal data |

| News articles | High | Protected creative content |

| Blog posts and editorial content | High | Reproduction can infringe copyright |

| Images and videos | High | Strong copyright protection |

| Aggregated statistics | Low | Typically non-expressive |

The safest scraping strategies focus on factual, non-expressive data and apply strong filtering before data enters AI pipelines.

Data Ethics and Responsible Scraping

Legal compliance defines what is permitted. Data ethics defines what is appropriate. Ethics fills that gap by guiding how organizations behave when rules are unclear. Responsible scraping is not about avoiding value creation. It is about ensuring that value is created without causing harm, overreach, or unintended consequences. For AI pipelines, ethical discipline matters because models amplify whatever they are trained on. Poor choices upstream rarely stay isolated.

Figure 2: How legality, ethics, and governance intersect in real-world web scraping and AI data pipelines.

Another ethical dimension is proportionality. Automated access should not degrade the performance or availability of source platforms. Responsible pipelines regulate crawl frequency, distribute load, and respect signals that indicate discomfort or restriction.

Transparency explains how data teams use their collection logic internally and externally. This clarity builds trust, especially when AI outputs influence pricing, hiring, or recommendations that affect real people.

Ethics also intersects with consent and representation. Some datasets reflect communities, opinions, or behaviors. Extracting and using this data without context or safeguards can reinforce bias or misinterpretation. Ethical pipelines apply review layers that look beyond legality and ask whether the use aligns with the intended purpose.

Common Legal and Compliance Mistakes Teams Make When Scraping

Over-collecting fields

Pipelines frequently collect more fields than the use case requires. Extra fields increase exposure to privacy and copyright risk and make compliance harder to manage. Minimal collection reduces both risk and noise.

Assuming one region’s rules apply everywhere

Global pipelines often reuse the same logic across regions. This creates blind spots where local laws impose different expectations around consent, retention, or data localization.

No review when sources change

Websites evolve. Terms update. Access rules shift. Teams that never re-evaluate sources accumulate silent risk over time.

Table — Common Scraping Mistakes and Their Impact

| Mistake | Why It Happens | Resulting Risk |

| Assuming public data is free to use | Oversimplified understanding of legality | Copyright or contract disputes |

| Ignoring purpose limitation | Focus on collection, not usage | Compliance gaps during audits |

| Collecting unnecessary fields | “Just in case” mindset | Increased privacy exposure |

| Missing lineage documentation | Fast pipeline iteration | Inability to defend data usage |

| Reusing pipelines globally | Lack of regional review | Jurisdictional violations |

| No source revalidation | Static assumptions | Silent compliance drift |

Designing a Legally Defensible Web Scraping Workflow

Start with source qualification

Every source should pass a basic qualification step. This includes reviewing access rules, understanding usage restrictions, and identifying whether personal or creative content is present. Sources that introduce unnecessary risk should be excluded early rather than managed later.

Apply data minimization at ingestion

Only fields that directly support the stated purpose should enter the pipeline.

Monitor change continuously

Web sources change over time. A defensible workflow revisits assumptions regularly. Terms update. Structures shift. New regulations emerge. Pipelines must adapt or risk accumulating outdated practices.

Prepare for questions

The true test of defensibility is simple. Can the team explain the dataset to a third party without hesitation? If the answer is yes, the workflow is likely sound. If not, improvements are needed.

Designing for defensibility does not slow down data work. It prevents disruption later. Teams that invest early build pipelines that last longer, scale more safely, and support AI initiatives without constant legal uncertainty.

What Should Guide Web Scraping Decisions in 2025?

The global legality of web scraping is often framed as a risk conversation. That framing misses the point. Scraping becomes risky not because the web is off-limits, but because teams operate without clarity. When legality is treated as a vague threat rather than a set of concrete conditions, organizations either overstep or overcorrect.

What this article shows is that web scraping legality is contextual. Laws look at the type of data, the way it is accessed, the purpose it serves, and how responsibly it is handled over time. Public access does not guarantee free reuse. Automation alone does not create illegality. Compliance sits in the details, not in absolutes.

Across regions, the same pattern emerges. Regulators care about intent, proportionality, and safeguards. GDPR focuses on personal data and lawful processing. Copyright law distinguishes facts from creative expression. Courts assess whether access bypassed controls or caused harm. Ethics fills the gaps where law has not fully caught up.

For teams working with AI, these distinctions matter even more. Models amplify upstream decisions. A dataset collected casually can become a long-term liability once it powers predictions, pricing, or recommendations. Conversely, a dataset collected with restraint and documentation becomes an asset that scales with confidence.

The organizations that succeed with web data do not look for shortcuts. They build workflows that are explainable, auditable, and adaptable. They collect only what they need. They document why it exists. They revisit assumptions as laws and platforms evolve. This approach turns legality from a blocker into a design constraint that improves quality and trust.

Web scraping is not about pushing boundaries. It is about understanding them well enough to work responsibly within them. When teams choose clarity over fear, web data becomes a reliable foundation rather than a source of uncertainty.

Further Reading From PromptCloud

If you want to go deeper into how legality, quality, and governance connect, these articles help extend the discussion:

- Learn how quality benchmarks influence compliance decisions in AI Data Quality Metrics 2025

- See how structured data supports safe AI training in Structuring and Labeling Web Data for LLMs

- Understand traceability as a legal and operational safeguard in Data Lineage and Provenance

- Compare risks across data sources in Synthetic Data vs Real Web Data for AI Training

For a clear legal perspective on how courts assess web scraping, public data access, and automated collection, refer to the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s legal analysis: Web Scraping and the Law – What the Courts Say.

PromptCloud helps build structured, enterprise-grade data solutions that integrate acquisition, validation, normalization, and governance into one scalable system.

FAQs

Is web scraping legal in all countries?

There is no universal rule. Legality depends on jurisdiction, data type, access method, and intended use.

Does GDPR prohibit web scraping?

No. GDPR regulates personal data processing, not scraping itself. Non-personal data generally falls outside its scope.

Can publicly visible data still be restricted?

Yes. Public visibility does not remove copyright protection or contractual obligations defined by terms of service.

Is scraping allowed for AI training?

It depends on the data and how it is used. Factual, non-personal data carries lower risk than creative or personal content.

What makes a scraping workflow legally defensible?

Clear purpose, minimal collection, documentation, respect for access rules, and continuous review.