**TL;DR**

Scalable web scraping does not fail because of volume. It fails because systems assume uniform traffic, predictable sites, and linear growth. PromptCloud’s horizontal scaling model is built around variability instead. Queues absorb spikes, load balancers isolate failures, and elasticity ensures crawlers expand and contract without manual intervention. The result is distributed crawling that stays stable even when the web does not.

What is Scalable Web Scraping?

Most people think scalable web scraping is a math problem.

- More URLs means more crawlers.

- More crawlers means more servers.

- More servers means you scale.

That logic works right up until it doesn’t. Real-world scraping does not behave linearly. Traffic arrives in bursts. Sites throttle unpredictably. HTML structures change mid-run. Some domains crawl cleanly for weeks and then suddenly collapse under a minor change. Others behave well at low concurrency and break the moment you scale.

This is where many scraping systems fail. They are built for volume, not volatility. PromptCloud’s approach to scalable web scraping starts from a different assumption. The problem is not how many pages you crawl. The problem is how uneven, hostile, and unpredictable the web is at scale.

Horizontal scaling, in this context, is not just about adding more workers. It is about controlling pressure. Knowing where to buffer it. Knowing where to release it. And knowing when to stop pushing altogether.

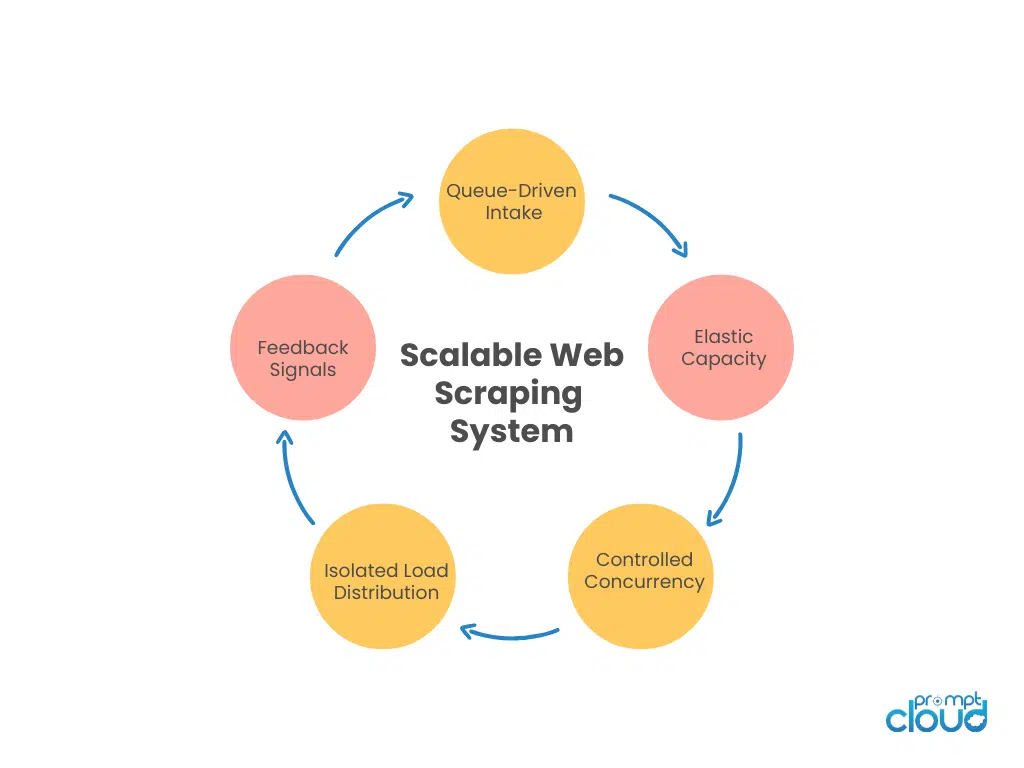

That is why queuing, load balancing, and elasticity are not separate components in PromptCloud’s architecture. They are tightly coupled control systems. Queues decide when work should happen. Load balancers decide where it should happen. Elasticity decides how much should happen at any moment.

Together, they allow distributed crawling systems to scale without becoming brittle. This pillar breaks down that logic. Not as a generic architecture diagram, but as an operational system built to survive real scraping conditions. We will walk through how work enters the system, how pressure is managed, how failures are isolated, and how crawlers scale horizontally without overwhelming targets or infrastructure.

Why Vertical Scaling Breaks First in Web Scraping Systems

Most scraping systems start vertically. Bigger machines. More CPU. More memory. Faster disks. It feels efficient at first because everything lives in one place and performance improves instantly. For a while.

Then traffic changes. A single domain slows down. Another spike unexpectedly. One parser hangs. One IP pool gets throttled. Suddenly the same machine that felt powerful becomes a shared point of failure.

Vertical scaling collapses under uneven load. Web scraping workloads are not uniform. One URL might take milliseconds. Another might take minutes. Some sites tolerate concurrency. Others punish it. Vertical systems assume predictability. The web does not offer it.

This mismatch shows up fast.

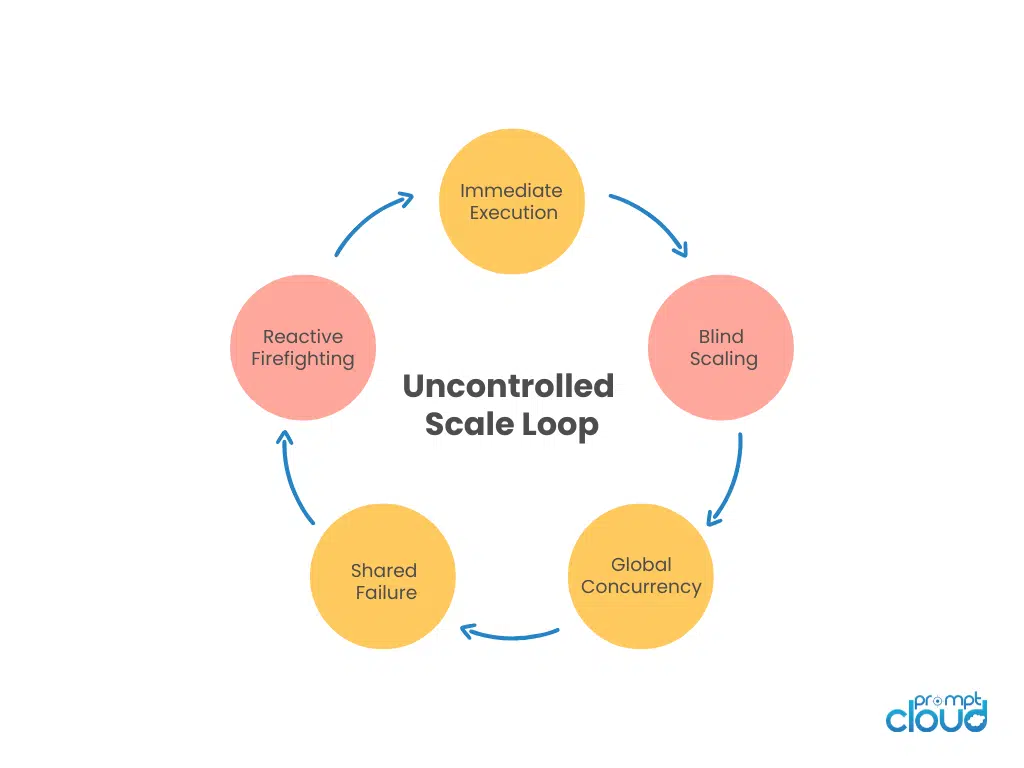

CPU spikes are not evenly distributed. Memory pressure comes from a handful of problematic pages. Thread pools clog because one task misbehaves. When everything shares the same process space, failure spreads sideways.

The deeper problem is control. Vertical systems blur boundaries. You cannot easily pause one workload without affecting others. You cannot isolate a slow domain without throttling the entire system. You cannot absorb traffic spikes without overprovisioning permanently. Teams respond by adding safeguards. Timeouts. Retry limits. Circuit breakers. Eventually the system becomes a maze of exceptions. And still breaks. This is why scalable web scraping shifts away from vertical thinking early. Not because vertical scaling is wrong, but because it is the wrong abstraction for a volatile environment.

Horizontal scaling introduces separation. Work can be queued instead of executed immediately. Crawlers can fail without taking others down. Domains can be isolated. Capacity can expand where pressure exists, not everywhere at once. The moment you introduce queues and distributed workers, the system gains leverage. You stop reacting to spikes and start absorbing them.

This is the foundation PromptCloud builds on. Before talking about auto scaling crawlers or concurrency models, you need to accept one thing. Scraping systems do not fail because they are too small. They fail because they cannot control where pressure builds. Horizontal architecture is how that control begins.

Figure 2: The failure loop that emerges when horizontal scaling lacks queues, isolation, and feedback control.

Turn your scraping pipeline into something you can trust under change with PromptCloud

The Role of Queuing in Scalable Web Scraping

Queues are the most misunderstood part of scraping architecture. Many teams treat queuing as plumbing. Something you add so tasks do not get lost. In scalable web scraping, queues are not plumbing. They are the control plane. A queue decides when work is allowed to happen. That distinction matters.

Why immediate execution fails at scale

In small systems, URLs are fetched as soon as they are discovered. That feels efficient. No waiting. No buffering. At scale, this approach collapses. Discovery and execution run at different speeds. One source might generate millions of URLs quickly. Execution might be limited by site latency, throttling, or parsing cost. When you tie the two together, pressure has nowhere to go except into your workers. Queues create separation. Discovery can run ahead without overwhelming execution. Execution can slow down without blocking discovery. The system breathes.

Queues as pressure absorbers

In PromptCloud’s architecture, queues exist to absorb volatility. Traffic spikes. Client demand surges. A crawl job expands unexpectedly. Instead of forcing crawlers to keep up in real time, queues hold the excess. This is not delay for delay’s sake. It is controlled pacing. By letting queues grow temporarily, the system avoids making bad decisions under pressure. Crawlers are not forced to overload targets. Infrastructure is not forced to scale blindly. Everything downstream remains stable.

Priority and fairness matter

Not all crawl tasks are equal. Some are time-sensitive. Some are long-running. Some target fragile sites. Some can tolerate retries. A single flat queue treats them all the same. That is a mistake. Scalable systems use multiple queues or priority lanes. Time-critical jobs move first. Sensitive domains are throttled deliberately. Heavy jobs are isolated so they do not starve lighter ones. This is where queuing logic starts to look less like infrastructure and more like policy.

Backpressure is a feature, not a failure

When queues grow, it is tempting to panic. But queue depth is information. It tells you where demand exceeds capacity. It tells you which domains are slow. It tells you when scaling is needed and when it is not. PromptCloud uses queue metrics as signals. They feed directly into elasticity decisions. Scale up when queues indicate sustained pressure. Scale down when they drain naturally. This avoids reactive scaling based on short-lived spikes.

Queues protect everything else

Without queues, every other component becomes brittle. Load balancers are forced to route more traffic than workers can handle. Auto scaling crawlers spin up too aggressively. Failures cascade because nothing slows the system down. Queues create a buffer between intent and action. That buffer is what makes distributed crawling manageable.

Load Balancing: Distributing Crawl Work Without Spreading Failure

Load balancing in scraping is not about spreading traffic evenly. Even distribution is what you do when tasks are similar. Scraping tasks are not similar. They vary by domain behavior, response times, parsing cost, login requirements, and bot defenses. If you balance purely for “evenness,” you end up spreading pain, not efficiency. The real job of load balancing in scalable web scraping is isolation. You want traffic to flow where it should, and you want failures to stay where they start.

What makes scraping load balancing different

Traditional load balancing assumes:

- requests are short

- failures are rare

- backends behave similarly

- retries are cheap

Scraping breaks all of that. Requests can hang. Retries can trigger blocks. Backends are not identical because workers may be configured differently for different sites, rendering needs, and proxy pools. So the load balancer cannot be dumb. It has to be policy-aware.

Domain-aware routing

The first major shift is routing by domain or source characteristics.

- If a domain is fragile, it should be routed to workers configured for lower concurrency and stricter pacing.

- If a domain requires rendering, route it to browser-capable workers. If a job is API-like and lightweight, route it to high-throughput workers.

This is how concurrency models become practical. Concurrency is not set globally. It is shaped by routing decisions.

Health checks that matter

A load balancer in this context must monitor more than uptime. A worker can be “up” and still useless. It might be stuck on a small set of long tasks. It might be suffering proxy failures. It might be experiencing elevated error rates because a specific domain is blocking. So health checks need to reflect scraping reality:

- queue lag per worker group

- error rate by domain

- median and tail latency

- retry inflation

- proxy pool health signals

When health checks become richer, routing becomes safer.

Preventing blast radius

One blocked domain should not degrade everything else.This is where isolation patterns show up: separate worker pools, separate queue lanes, separate proxy groups. The load balancer ties these together so the right work lands in the right place. When a domain starts failing, the system can:

- throttle that domain lane

- reroute away from overloaded workers

- pause retries to avoid escalating blocks

- keep unrelated workloads moving

This is how elasticity stays intelligent instead of reactive.

Table: Load balancing strategies for distributed crawling

| Load balancing approach | What it routes by | What it’s good for | Risk if misused |

| Round-robin | Worker count only | Uniform, lightweight tasks | Spreads failures, ignores domain behavior |

| Least connections | Active sessions | Mixed workloads, avoids overloaded workers | Can still route fragile domains to bad-fit workers |

| Domain-aware routing | Target domain or site class | Bot-sensitive sites, per-domain pacing | Requires good site classification and monitoring |

| Capability-based routing | Worker capabilities (browser, JS, geo, proxies) | Rendering-heavy targets, login flows | Complexity if capabilities drift or aren’t enforced |

| Queue-lane routing | Priority or job lane | Time-sensitive vs bulk jobs | Starvation if priorities aren’t tuned |

| Fail-open with circuit breakers | Health signals and error thresholds | Preventing cascading failures | Can drop coverage if thresholds too aggressive |

This is the central idea. Load balancing is not a single algorithm. It is a set of routing rules tied to what the web is doing right now.

Elasticity Logic: How Auto Scaling Crawlers Expand Without Overshooting

Auto scaling crawlers sound simple on paper.

- Traffic goes up.

- Spin up more workers.

- Traffic goes down.

- Shut them off.

That logic is fine for predictable workloads. Scraping is not one.

In scraping systems, demand spikes rarely mean you should scale immediately. They often mean something else is happening. A slow domain. A temporary block. A retry storm. A malformed page that suddenly takes ten times longer to parse. If you scale blindly, you amplify the problem. Elasticity in scalable web scraping has to be conservative by design.

Scaling signals come from queues, not traffic

PromptCloud’s elasticity logic does not watch raw request volume. It watches sustained pressure.

- Queue depth over time.

- Drain rate versus arrival rate.

- Backlog growth patterns.

Short spikes are ignored. Sustained imbalance is acted on. This avoids the classic mistake where auto scaling crawlers react to noise instead of load. The system waits to understand whether demand is real before committing resources.

Scale in layers, not jumps

When elasticity kicks in, it does not flood the system with workers. Capacity is added in small, controlled increments. Each increment is observed. If queues start draining faster and error rates remain stable, the next increment is allowed. If not, scaling pauses. This layered approach matters because adding crawlers also adds pressure on targets. Scaling too aggressively can trigger rate limits or blocks that make things worse. Elasticity here is about restraint.

Scale differently for different work

Not all crawling pressure should be relieved the same way. Some backlogs come from heavy rendering jobs. Some from simple fetches. Some from retry-heavy domains. Scaling the wrong worker pool wastes capacity and increases failure.

This is where elasticity ties back to load balancing. Auto scaling crawlers are grouped by capability. Rendering workers scale independently from lightweight fetchers. Geo-specific pools scale independently from global pools. Domain-sensitive lanes scale with stricter rules. Elasticity follows the shape of the workload, not a global counter.

Know when not to scale

This is the hardest part. Sometimes the right response to pressure is to slow down, not speed up. If a domain starts returning blocks, scaling crawlers just increases block volume. If retries explode, scaling multiplies retries. If proxy health degrades, scaling amplifies bad signals. PromptCloud’s elasticity logic includes negative signals. Rising error rates. Increasing retry depth. Proxy pool degradation. When these appear, scaling is suppressed even if queues grow. This is counterintuitive, but essential. A system that always scales up will eventually collapse.

Scale-down is just as deliberate

Scaling down is not an afterthought. Workers are drained gracefully. In-flight tasks complete. Queue lanes rebalance. Capacity is reduced slowly to avoid oscillation. This prevents the system from thrashing between over- and under-provisioned states.

Elasticity is about stability, not speed

The goal of auto scaling crawlers is not to finish faster at any cost. The goal is to finish reliably. Elasticity works when it smooths variability instead of chasing it. When it keeps systems inside safe operating bounds instead of pushing them to limits. This is how scalable web scraping stays stable under real-world conditions.

Concurrency Models in Distributed Crawling

Concurrency is where scalable web scraping gets real. It is also where teams break things by being “efficient.” Most people treat concurrency like a knob. Turn it up. Get more throughput. Done. In distributed crawling, concurrency is a contract. With your infrastructure, with your proxy pools, and with the target websites. Break that contract and the system will still run, but it will stop being reliable. PromptCloud treats concurrency as a model, not a number.

Why a single global concurrency limit fails

A global concurrency setting assumes all targets behave similarly. They do not. One site can tolerate hundreds of parallel requests. Another triggers blocks after ten. Some pages are static. Some require rendering. Some are fast. Some are slow and unpredictable. If you set concurrency high enough to satisfy fast targets, you punish fragile ones. If you set it low enough to protect fragile ones, you waste capacity on fast ones. So a mature architecture uses multiple concurrency models depending on the workload and the target’s behavior.

The most common concurrency models

| Concurrency model | How it works | Where it fits best | Where it breaks |

| Global worker pool concurrency | A fixed max in-flight requests across all work | Small systems, uniform targets | Mixed targets, fragile domains, varied page cost |

| Per-domain concurrency caps | Each domain has its own max parallelism | Bot-sensitive or rate-limited sites | Hard if domains are misclassified or change behavior |

| Token bucket rate limiting | Requests “spend” tokens; tokens refill over time | Stable pacing, predictable load | Needs tuning, can underutilize capacity if too strict |

| Leaky bucket throttling | Smooths bursts into a steady output | Preventing spikes, avoiding bans | Can introduce backlog if demand is bursty |

| Priority lane concurrency | Separate pools for urgent vs bulk work | SLA-driven crawl jobs | Starvation risk if priorities never rebalance |

| Capability-based concurrency | Concurrency differs by worker type (browser vs non-browser) | Mixed render + fetch workloads | Complexity if routing and pool sizing are wrong |

| Adaptive concurrency | System adjusts based on error rates and latency | Volatile targets, changing behavior | Requires good monitoring, can oscillate if noisy signals |

The key point is this. Concurrency is not one thing. It is a set of pacing strategies.

Concurrency must be tied to failure signals

A concurrency model becomes intelligent when it reacts to the right signals. Not just CPU usage. Scraping systems need to watch:

- rising 429s and 403s

- sudden increases in latency

- retry inflation

- proxy failure rates

- response size anomalies

- session instability for logged-in flows

When these signals worsen, concurrency should fall automatically. When they stabilize, it can rise slowly.

This is how distributed crawling stays stable while still pushing throughput.

Concurrency must respect the entire pipeline

Even if the target can handle high parallelism, your system might not. Rendering capacity. Parser throughput. Storage write rates. Queue consumption. Downstream validation steps. One overloaded stage will back up everything else. This is why concurrency is often set by the slowest constraint, not the fastest target. In PromptCloud-style architectures, concurrency decisions are made with the full pipeline in mind, not just the fetch stage.

The practical outcome

When concurrency models are designed well:

- fast sites stay fast

- fragile sites stay stable

- blocks reduce

- retries shrink

- throughput becomes predictable

That predictability is the real value of scalable web scraping.

What a Strong Vendor Compliance Checklist Must Cover

A useful vendor compliance checklist does not try to cover everything. It covers the things that actually fail in real vendor relationships. The goal is not completeness. It is risk visibility.

Data handling comes first

If a vendor touches your data, data handling deserves the most attention. A checklist should clearly ask:

- What data is collected and from where

- Whether personal or sensitive data can appear, intentionally or accidentally

- How data is filtered, masked, or anonymized

- Where data is stored and for how long

This is where many audits stay vague. “We handle data securely” is not an answer. A checklist should require specifics, ideally backed by examples or documentation. For vendors involved in automated collection or enrichment, it helps to align these questions with privacy-safe practices. This overview of privacy-safe scraping and PII masking explains the kinds of controls that should show up during audits.

Governance and accountability need to be explicit

Good vendors can explain who is responsible when something goes wrong. A checklist should ask:

- Who owns data governance internally

- How decisions around access, reuse, and deletion are made

- What escalation paths exist for incidents or disputes

- How changes to scope or data sources are approved

If responsibility is vague, accountability usually is too.

Risk mitigation is more than security controls

Security questions are important, but they are not enough on their own. A strong checklist looks at risk holistically. Operational risk, legal risk, and reputational risk all matter. How quickly can a vendor respond to an issue? How transparent are they when something breaks. How do they communicate changes that might affect compliance. These answers often matter more than certifications.

Evidence matters more than promises

One of the simplest ways to strengthen a checklist is to ask for evidence. Logs. Sample reports. Incident response summaries. Audit artifacts. Even anonymized examples help. Vendors that operate mature systems usually have this material ready. Vendors that rely on manual processes often struggle. That difference is a valuable signal.

The checklist should be usable, not theoretical

Finally, a checklist should be practical. Questions should be clear enough that different reviewers interpret them the same way. Answers should be comparable across vendors. Follow-up actions should be obvious. If a checklist cannot be reused across vendors and over time, it will slowly be ignored.

Designing the Checklist: Categories and Structure That Work

Once you know what needs to be covered, the next challenge is structure. This is where many teams overcomplicate things. They create long documents filled with overlapping questions, legal language, and vague scoring. The result looks thorough but is hard to use. A good vendor compliance checklist is structured to be answered, reviewed, and revisited.

Start with clear sections, not random questions

The checklist should be grouped into a small number of logical categories. This helps reviewers focus and helps vendors understand what is being evaluated. A practical structure usually includes:

- Data collection and handling

- Privacy and compliance controls

- Security and infrastructure

- Governance and accountability

- Operational resilience

- Auditability and evidence

Each section should answer a simple question. Can this vendor be trusted with this aspect of our operations? If a section does not map to a clear risk area, it probably does not belong.

Keep questions specific and testable

Checklist questions should be written so they can be answered clearly. Avoid questions that invite marketing language. “Do you follow best practices?” rarely produces useful information. Instead, ask questions that force detail. How is access controlled? Where are logs stored? How long is data retained. What happens when a policy changes. Specific questions reduce ambiguity and make follow-up easier.

Design for comparison, not perfection

One of the most useful outcomes of a vendor compliance checklist is comparison. You want to see where vendors differ, not just whether they pass. That means questions should be consistent across vendors and phrased in a way that makes differences obvious.

This is especially important when vendors play similar roles but use different approaches, such as batch versus real-time data delivery. If your organization relies on time-sensitive data, understanding how vendors manage change and availability becomes critical. This discussion on staying ahead with real-time data shows why operational discipline matters as much as feature sets.

Leave room for evidence and notes

A checklist should not just collect answers. It should collect context.

Each section should allow reviewers to note evidence, concerns, and follow-up actions. This is what turns a checklist into a working audit record instead of a static form. Over time, these notes become valuable history. They show how vendors evolve and where risk has increased or decreased.

Make it reusable by default

The best checklists are reused. They are updated as regulations change. They are applied when scope expands. They are referenced when incidents occur. Designing for reuse means keeping language clear, avoiding one-off assumptions, and treating the checklist as part of governance, not procurement paperwork.

Running the Audit: How to Use the Checklist Effectively

A vendor compliance checklist only creates value if it is used well. Many teams build solid checklists and then weaken them during execution. Questions are skipped to save time. Evidence is promised later. Follow-ups are left open-ended. Over time, the checklist becomes ceremonial. Running the audit properly requires discipline, not aggression.

Treat the checklist as a working document

The checklist should guide the conversation, not sit beside it. Each question should be answered in writing. Verbal assurances should be captured and validated later. If an answer is unclear, that uncertainty should be recorded, not smoothed over. This creates a shared reference point. Weeks or months later, there is no debate about what was said or assumed.

Ask for evidence at the right moments

Evidence does not need to be exhaustive, but it should be targeted. If a vendor claims automated controls, ask for logs or architecture diagrams. If they claim compliance processes, ask for examples of how changes are handled. If they claim strong governance, ask who signs off on exceptions. The goal is not to overwhelm vendors. It is to see whether controls exist beyond policy language.

Use the audit to surface trade-offs

Not every gap is a deal-breaker. A good audit makes trade-offs explicit. A vendor might be strong on security but weaker on auditability. Another might be transparent but less automated. The checklist helps teams decide consciously instead of discovering trade-offs accidentally later.

Document outcomes and next steps

Every audit should end with clear outcomes. What risks were accepted. What gaps need remediation. What follow-ups are required. What timeline applies. Without this step, audits feel complete but change nothing.

Example: Vendor audit checklist in action

| Checklist area | Question asked | Vendor response | Evidence reviewed | Risk level | Follow-up action |

| Data handling | Can personal data appear in collected datasets | Yes, in edge cases | Sample dataset with masked fields | Medium | Confirm masking happens at ingestion |

| Privacy controls | How is PII masked or anonymized | Automated masking rules | Pipeline diagram and logs | Low | None |

| Governance | Who approves data reuse | Data governance committee | Internal policy document | Medium | Request escalation workflow |

| Security | How is access controlled | Role-based access | Access control list | Low | None |

| Auditability | Can you show lineage for a dataset | Partial lineage available | Sample lineage report | Medium | Request full lineage coverage |

| Operations | How are incidents handled | Manual escalation | Incident summary | Medium | Review response SLAs |

This kind of table keeps the audit grounded. It shows where risk exists and what is being done about it.

Why this approach holds up over time

Audits run this way and scale better. They are easier to repeat. Easier to compare. Easier to defend. When vendors change, the checklist adapts. When questions arise later, decisions are documented. That is the real payoff of a vendor compliance checklist. Not compliance theater, but durable risk management.

Where Vendor Audits Commonly Miss Risk

Even teams with solid checklists tend to miss the same kinds of risk. Not because the questions are wrong, but because attention drifts to what is easy to verify instead of what actually breaks. This section is about those blind spots.

Over-indexing on certifications

Certifications feel reassuring. ISO. SOC. Compliance badges. They matter, but they are not a substitute for understanding how a vendor actually operates day to day. Certifications describe controls at a point in time. They do not explain how those controls behave under pressure, change, or scale. A vendor can be certified and still struggle with data drift, delayed deletions, or undocumented reuse. Audits that stop at certificates miss operational reality.

Treating data outputs as the only risk surface

Many audits focus heavily on what data the vendor delivers. Much less attention is paid to how that data is produced. Where does it originate? What happens before transformation. What temporary storage exists. What logs are retained. Who can see raw inputs? This is especially risky for data vendors, where upstream collection methods and intermediate systems often carry more exposure than the final dataset. A proper data audit looks upstream, not just at what lands in your warehouse.

Ignoring change management

Vendors evolve. They add sources. They change infrastructure. They refactor pipelines. They onboard new teams. Each change can quietly alter risk. Audits often capture a snapshot and then assume stability. That assumption is rarely correct. Strong checklists ask how changes are reviewed, communicated, and approved. Weak ones assume today’s answers will still be true next quarter.

Assuming internal use means low risk

Another common miss is internal reuse. Teams assume that if data stays internal, risk is limited. In practice, internal reuse is where scope creep happens fastest. New teams access old datasets. New use cases emerge. Old assumptions are forgotten.

Vendor audits should ask how internal access is controlled and how reuse decisions are governed, not just whether data is shared externally.

Underestimating exit and offboarding risk

Most audits focus on onboarding. Very few focus on exit. What happens to data when a vendor relationship ends. How quickly can access be revoked? How is deletion verified? What evidence is provided. Offboarding is where weak governance shows up clearly. If a vendor cannot explain this cleanly, risk remains even after the contract ends.

Why these misses repeat

These gaps persist because they are uncomfortable. They require deeper questions. They slow down decisions. They surface trade-offs teams would rather avoid. But these are exactly the areas where real risk lives. A vendor compliance checklist that does not address them creates confidence without control.

Putting It Together: The Horizontal Scaling Control Loop

At this point, the pieces should feel familiar.

- Queues absorb pressure.

- Load balancers decide where work flows.

- Elasticity controls how much capacity exists.

- Concurrency models define how aggressively work executes.

On their own, each solves a problem. Together, they form a control loop. That loop is what makes horizontal scaling work in real-world scraping.

The loop starts with demand, not execution

Everything begins when new crawl demand enters the system. URLs are discovered. Jobs are scheduled. Client requests arrive. None of this triggers immediate execution. It feeds queues. This matters because it decouples intent from action. The system acknowledges demand without committing resources prematurely. Queues become the first signal surface.

Queues feed routing decisions

As queues grow or drain, the system learns where pressure exists.

- Which domains are backing up?

- Which job types are lagging?

- Which lanes are healthy?

Those signals inform the load balancer. Work is routed to worker pools that can actually handle it. Fragile domains are isolated. Heavy jobs avoid lightweight pools. Priority lanes move first. Routing decisions are continuous, not static.

Routing exposes capacity gaps

Once work is flowing to the right places, capacity limits become visible. Some pools drain their queues quickly. Others struggle. Some error rates rise. Others stay flat. This is where elasticity enters. Auto scaling crawlers are triggered by sustained imbalance, not momentary spikes. Capacity expands where queues remain stubbornly full and error signals stay clean. It does not expand everywhere. Elasticity is targeted.

Capacity changes feed back into concurrency

New workers do not automatically increase pressure. Concurrency limits still apply. Per-domain caps remain. Adaptive throttles remain active. If a target is already unhappy, scaling does not make it angrier. This feedback loop prevents the classic failure mode where adding workers causes more retries, more blocks, and longer runtimes. Scaling without control is just faster failure.

Negative feedback keeps the system stable

Every good control loop needs brakes.

- Error rates are rising.

- Latency spiking.

- Proxy pools degrading.

These signals reduce concurrency, pause scaling, or even shed load temporarily. The system backs off instead of doubling down. This is why PromptCloud’s horizontal scaling logic feels conservative from the outside. It is not trying to win bursts. It is trying to survive variability.

Why this loop matters

Without a control loop, horizontal scaling becomes guesswork. Teams scale reactively. They chase metrics. They add capacity hoping things improve. Sometimes they do. Often they do not. With a control loop, the system makes fewer decisions, but better ones. It responds to sustained patterns instead of noise. It treats pressure as information, not panic. That is the difference between a system that scales in demos and one that scales every day.

Figure 1: The core control signals that keep horizontally scaled scraping systems stable under variable load.

Why Horizontal Scaling Is an Operating Discipline, Not an Architecture Choice

By now, one thing should be clear. Scalable web scraping is not achieved by picking the right cloud service or adding more machines. It is achieved by deciding, repeatedly and deliberately, how the system should behave when the web does not cooperate. That is what horizontal scaling really is at PromptCloud. An operating discipline.

Queues are not there to delay work. They exist to give the system time to think. Load balancers are not there to maximize utilization. They exist to prevent failure from spreading. Elasticity is not there to chase speed. It exists to add capacity only when it is safe to do so. Concurrency models are not tuned once and forgotten. They are continuously shaped by what targets, proxies, and pipelines can actually handle.

All of these decisions are boring in isolation. Together, they are what keep large-scale crawling systems alive. This is also why scalable web scraping looks slower than expected from the outside. It waits. It backs off. It ignores short-term spikes. It refuses to turn every problem into a scaling event. That restraint is intentional. At scale, speed without control becomes fragility. Throughput without isolation becomes cascading failure. Automation without feedback becomes noise.

PromptCloud’s horizontal scaling model is built to avoid those traps. It assumes the web will change mid-run. It assumes targets will misbehave. It assumes demand will arrive unevenly. Instead of fighting those realities, the system absorbs them.

That is the real measure of scalability. Not how fast you can crawl on a good day. But how calmly your system behaves on a bad one. When queuing, load balancing, elasticity, and concurrency are treated as a single control loop instead of separate features, distributed crawling stops feeling risky. It becomes predictable. And predictability, at scale, is what clients actually care about.

For a neutral, systems-level perspective on scaling distributed workloads and control loops, this is a solid reference: Google SRE Handbook on handling load, backpressure, and elasticity. This reinforces the idea that queues, backpressure, and conservative scaling are stability mechanisms, not performance hacks.

Turn your scraping pipeline into something you can trust under change with PromptCloud

FAQs

What does scalable web scraping actually mean at enterprise scale?

It means the system stays stable as demand, sites, and conditions change. Throughput matters, but predictability matters more.

Why are queues so important in distributed crawling?

Queues decouple discovery from execution. They absorb spikes, expose pressure, and prevent workers from being overwhelmed.

How do auto scaling crawlers avoid over-scaling?

By reacting to sustained queue pressure and error signals, not raw traffic. Scaling is gradual and reversible.

Is higher concurrency always better for scraping?

No. Concurrency must match target behavior, proxy health, and pipeline capacity. Too much concurrency causes blocks and retries.

What usually breaks first in poorly scaled scraping systems?

Isolation. A single slow domain or failure mode spreads across workers and drags everything down.